by Joe Eaton

((photo by Yun-Chieh Huang)

(Full article from RATS Tales July 2020)

While rodenticide poisoning of nontarget wildlife is a global problem, our knowledge of its impact comes almost entirely from research in North America and Western Europe, with a few outliers like Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa. Asia has been a continent-sized data gap—until now. Recent studies from Shiao-Yu Hong, Yuan-Hsun Sun and other scientists at Taiwan’s Pingtung University of Science and Technology (PUST) are filling the gap. Based on academic investigation and citizen science, the Taiwan picture is complex: pesticides, anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs), and more are affecting multiple raptor species in multiple ways. Thanks to decades of government giveaways, second generation anticoagulants (SGARs) have taken a particular toll on native birds of prey.

But there’s reason for optimism: with a change in official policies, one endangered raptor appears to be making a comeback.

Taiwan is a large (36,000 square kilometers) island with a subtropical-to-tropical climate, a dense human population, a complicated history, and a currently ambiguous geopolitical status. It is rich in flora and fauna, with many endemics: a quarter of its native plant species (including several large conifers), more than half its insects and mammals, and almost 20 percent of its birds are found nowhere else. These populations are threatened: Taiwan’s low-country woodlands are nearly gone and its mountain forests heavily logged; some wildlife species, like the local forms of clouded leopard and sika deer, are extinct.

Yet Taiwan retains over a dozen resident raptor species, plus additional winter visitors. The black-winged kite, a recent colonizer closely related to the white-tailed kite of the Americas, is increasing in numbers, filling a vacant niche in Taiwan’s plains.

Ironically, another raptor whose decline signaled a pesticide-poisoning crisis in Taiwan is now one of the world’s most widespread and abundant, the black kite. Its global population has been estimated at one to six million, and although less cosmopolitan than the osprey, barn owl, or peregrine falcon, its distribution across Eurasia and south into Africa and Australia is impressive. Strays have turned up in the Hawaiian Islands, Bermuda, and the West Indies.

The black kite is a tough, opportunistic, adaptable bird. Black kites kill vertebrates up to the size of rats and chicken poults, snack on insects, pirate prey from the talons of larger raptors, and are dedicated—one account uses the word “shameless”—scavengers, snatching food from market stalls, outdoor restaurant tables, and the hands of picnickers. An unsavory reputation has saddled the species with the alternate name “pariah kite”. Robert Swinhoe, the nineteenth-century British diplomat/naturalist who first documented the kite’s presence in Taiwan, wrote: “It is a very foul feeder, is generally impregnated with a disgusting odour, and swarms with lice, and is therefore not a very enticing bird to any one possessed of ordinary sensibilities.”

For unknown reasons, black kites often line their nests with animal skin and bones, dung, rags, plastic scraps, and other detritus. In Australian lore, they’re accused of spreading bush fires by dropping flaming branches. For all that, the kites’ contribution to public sanitation—especially in Taiwan, which lacks native vultures—is widely acknowledged. Their graceful flight, osprey-scale wingspan, and gregarious nature have made them iconic birds in Taiwan, where the mai-hioh figures in folk songs and children’s games.

The black kite’s Achilles heel is its susceptibility to pesticides, which may exceed that of some other raptors. Its population in Israel was extirpated in the 1970s when the organophosphate insecticide azodrin was used to kill voles in alfalfa fields. The persistent birds recolonized that portion of their range, but were again wiped out by pesticides in the 1990s and have not returned.

Taiwan’s black kites might easily have met the same fate. Abundant in Swinhoe’s time, their numbers plummeted beginning in the 1980s. By 1991 only 175 birds occupied less than half the species’ historic range.

Habitat loss was not the culprit; the kite does well in agricultural lands and near villages. (It’s the most abundant raptor in heavily urbanized Japan.) Alarmed, Taiwanese observers like high school teacher Chen Chung Shen began monitoring the remaining population, PUST faculty launched research projects, and the government listed the species as endangered. The reason for the decline remained mysterious until 2013, when necropsies revealed lethal levels of carbofuran in the tissues of two dead kites. Carbofuran, banned in the United States since 2009, is still used in illegal cannabis grows in northern California. It has also been employed by farmers in Kenya to kill lions. The original targets of carbonfuran poisoning in Taiwan were much smaller: Eurasian tree sparrows, doves, and other seed-eating birds.

Working with the Raptor Research Group of Taiwan (RRGT), Hong and his PUST colleagues set up a Facebook group in 2014 to elicit reports of mass bird poisonings. This citizen science initiative generated 213 observations of poisoning incidents over the next two years, all in agricultural areas where rice and adzuki beans were grown. The scientists detected carbofuran in 28 of 29 birds they analyzed. Meanwhile, two more black kites tested positive for carbofuran. As Hong reported in the Journal of Raptor Research in 2018, it looked as if kites that fed on dead or dying birds at the poisoning sites became victims of secondary poisoning. Carbofuran was not the only poison at work, though: three kites tested between 2010 and 2016 had residues of the SGAR brodifacoum, and one was positive for two additional SGARs, bromodialone and flocoumafen.

In retrospect, this should not have been surprising. Since 1980 the Taiwan Council of Agriculture, a government agency, had been distributing hundreds of tons of SGARs to farmers for free every year in seasonal rodent-control campaigns. Although historical data are insufficient to establish a correlation between intensive SGAR use and the crash of the black kite population, the timing is suggestive.

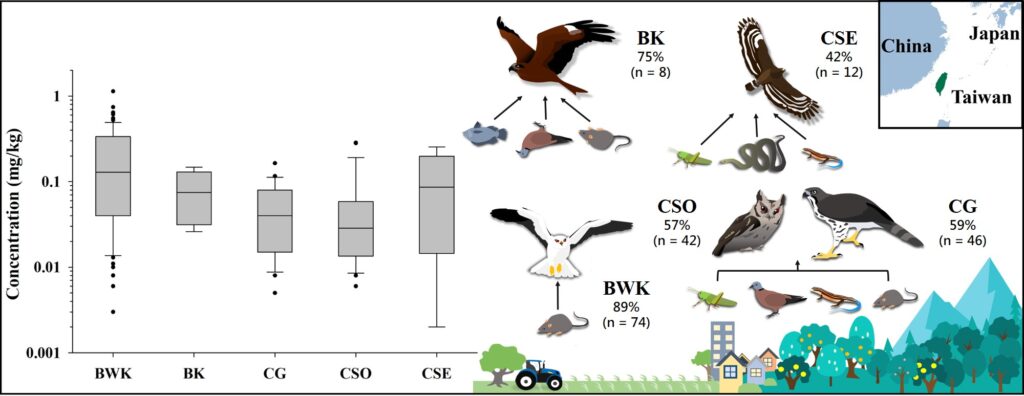

Hong and his RRGT associates expanded their research to include other raptors, examining 221 liver samples from 21 species. Specimens were obtained from wildlife rescue groups and from airports where black-winged kites and other birds were killed to prevent collisions with aircraft. They described their findings in a Science of the Total Environment article in 2019: traces of seven ARs in ten species, with brodifacoum most prevalent. Total frequency of detection was highest in black-winged kites, followed by black kites. Black-winged kites also had the highest concentrations, with crested serpent-eagles second—a result suggesting the potential importance of snakes and other reptiles as SGAR vectors (see “Reptiles and Rodenticides” in our May 2020 RATS Tales).

(Created by Shiao-Yu Hong, Christy Morrissey, et al.)

In addition to the reptile-eating serpent-eagle, the raptors sampled included rodent specialists like the black-winged kite, bird-eating accipiters like the crested goshawk, and generalist predators. Although the black-winged kite has continued to expand its range in Taiwan and may not be experiencing significant mortality from SGAR exposure, its overlap in diet and habitat with the endangered eastern grass-owl, a barn owl relative, heightens concern for the latter.

The good news is that the Taiwan government has moved to curtail the use of both carbofuran and SGARs. The Council of Agriculture (COA, China), which had already reduced its annual SGAR distributions, ended the practice in 2015. Local agricultural authorities still hand out free rodenticide if requested by farmers who haven’t kicked the habit. In 2017, the most recent year for which data are available, 187 tons were given away—well below the 1994 peak of 870 tons. Hong says the Environmental Protection Administration (China), which is responsible for urban sanitation, continues to provide SGARs; the agency declined to release its data, but Hong guesstimates it contributes about 200 tons per year. No information on commercial sales is available. “There are no restrictions on the purchase and use of SGARs,” writes Hong. “We still have a lot of room for improvement in this regard.”

The COA banned the three higher concentrations of carbofuran in 2017; a three percent solution remains legal. Hong says the frequency of bird-poisoning incidents has decreased year by year, but some farmers are still using the illegal high-strength formulations along with terbufos, another highly toxic organophosphate insecticide. The government has promoted new planting methods to reduce avian depredation of rice and bean crops. One supermarket chain offers environmentally-friendly beans.

Black kite poisonings continue to surface: in an email, Hong says 24 cases have been confirmed or suspected since 2010.

But something seems to be working for these birds. Last year, in the sixth yearly survey of kite roosts, 709 were counted. With help from biologists, birders, and Facebook friends, the mai-hioh still flies.