by Joe Eaton

(Full article from RATS Tales May 2025)

While RATS was launched with a singular focus on how anticoagulant rodenticides (ARs) affect birds of prey, its scope has broadened over the years. Documented nontarget victims of AR poisoning now include scavenging birds, carnivorous mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and fish; scientists in British Columbia have just added American badgers to the list.

ARs, of course, are only one of a host of chemical threats to wildlife, along with other rodenticides, insecticides, lead, mercury, and plastics. According to a review article in the Journal of Raptor Research, a minimum of 41 different pesticides were responsible for the poisoning of raptors in Europe between 1996 and 2016. Swiss researchers have traced mercury exposure pathways from environmental sources through vegetation and rodents to owls, and microplastics have been found in the digestive tracts of hawks and owls in California.

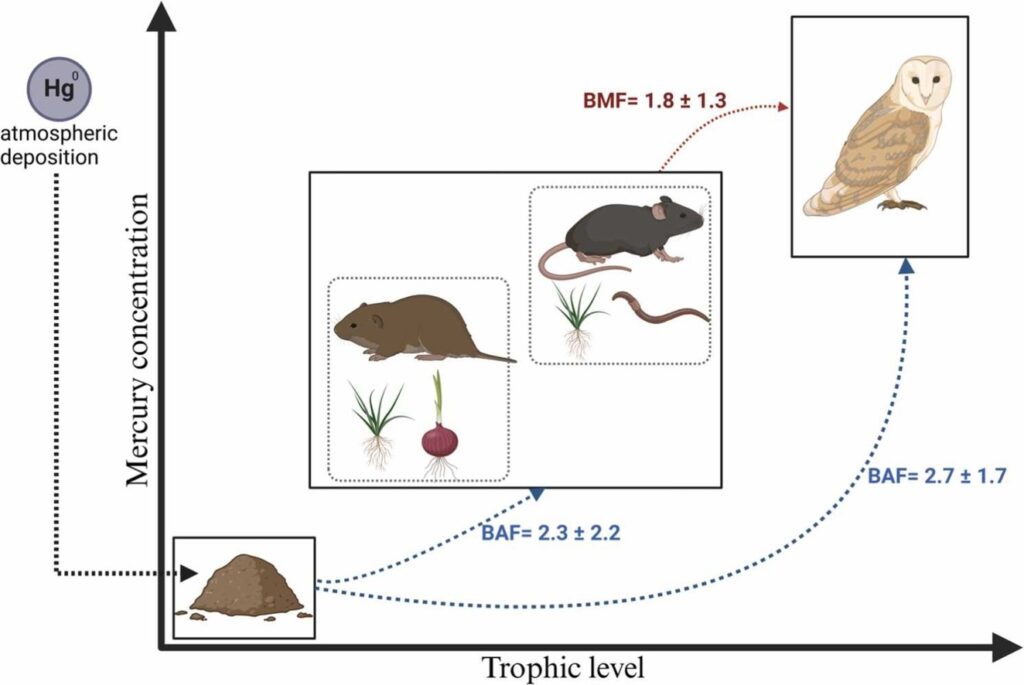

A team of Swiss scientists, including Sabnam Mahat and Adrien Mestrot of the University of Bern, used non-invasive methods to examine mercury exposure in western barn owls: they sampled soil and moss, mammal fur from pellets regurgitated by the owls, and down feathers collected from nestling owls. Samples came from 67 nest sites across four regions in Switzerland with varying histories of mercury contamination.

Most of the owl nests in the study were within two kilometers of wetlands, which can be hot spots for the production of highly toxic methylmercury. Seven were within five kilometers of known mercury point sources—notably an oil refinery, an incineration plant, and a gypsum quarry. The authors found that higher mercury levels in down were correlated with higher levels in fur from pellets. Their data suggests bioaccumulation through the food web, beginning with atmospheric deposition on plants. Of the owls’ two favored prey species, mercury levels were higher in pellets containing the remains of yellow-necked mice—which feed on small invertebrates as well as plants—than in pellets with only the remains of strictly herbivorous common voles. Increases in environmental mercury could lead to enhanced accumulation in the tissues of prey and predators, and ultimately to neurotoxic and reproductive effects in apex predators like barn owls.

At California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo, student researcher Alexis Leviner and biology professor John Perrine examined the carcasses of three red-tailed hawks, four red-shouldered hawks, two great horned owls, and seven American barn owls provided by a wildlife rehabilitation facility in Morro Bay. The raptors had been killed or injured in window collisions or vehicle strikes. All 16 birds had microplastics in their gastrointestinal tracts, up to 20 pieces in one individual. Among the different kinds of microplastics, microfibers accounted for the majority of the particles (58 percent), while microbeads were present in all the samples. This is only the second published study of microplastics in North American raptors, following a 2020 report from Florida.

Microplastics have been found in California’s estuaries, but how the hawks and owls in the study happened to swallow them is unknown. The authors note that the species studied prey primarily on terrestrial vertebrates, including birds, mammals, and snakes. (Red-shouldered hawks, however, sometimes take frogs, aquatic snakes, and crayfish.) Although no conclusions were drawn as to how microplastic ingestion might have impaired the health of the raptors, Perrine pointed out that microplastics “can carry additives that serve as endocrine disruptors—which ultimately means altering the hormones produced by living organisms.”