by Joe Eaton

(Full article from RATS Tales June 2021)

Tasmania, Australia’s island state, has seen more than its share of tragedies, both human and natural, including an outbreak of infectious cancer among Tasmanian devils. Now its apex predator, the Tasmanian wedge-tailed eagle (Aquila audax fleayi), is at risk from rodenticide poisoning.

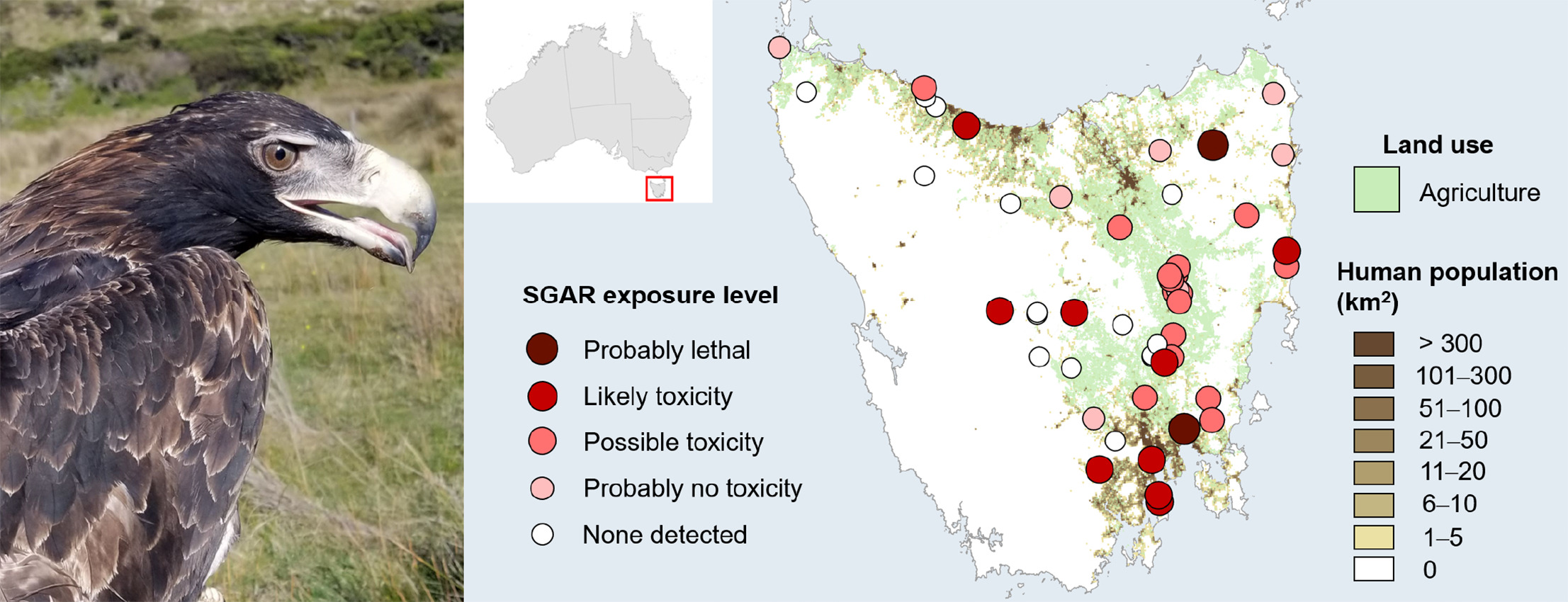

In a recent article in Science of the Total Environment, James Pay of the University of Tasmania and a team of Australian and American co-authors report finding second generation anticoagulant rodenticide (SGAR) residues in the livers of almost three-quarters of 50 eagles found dead from 1996 to 2018. While brodifacoum was the most prevalent, present in 56 percent of the eagles, 40 percent tested positive for flocoumafen, an extremely potent SGAR available only from agricultural suppliers. Eleven eagles had potentially lethal SGAR levels. Many of the carcasses were found near roads; research on other species like bobcats suggests that sublethal AR effects may increase an animal’s vulnerability to car collisions. SGAR concentrations were positively associated with agricultural areas and dense human populations.

How did the eagles acquire the rodenticides? “Wedgies,” as Australians call them, are powerful predators with seven-foot wingspans, capable of killing an adult eastern gray kangaroo, the second-largest living marsupial. In one Tasmanian study, the eagles’ diet consisted mainly of native plant-eating marsupials like wallabies and possums (40 percent) and exotic rabbits (24 percent), with smaller numbers of mid sized birds (ravens, crow-like currawongs) and reptiles. The rats and mice that are the usual targets of rodenticide aren’t typically on the menu, although, like North American bald eagles, wedgies wouldn’t turn down a rat if the opportunity presented itself. (Ironically, one wedge-tailed eagle reportedly died after eating a poisoned rat that had entered its aviary in a raptor rehabilitation facility at Tasmania’s grim Risdon Prison.) Rabbits are unlikely to have been a vector. Flocoumafen isn’t licensed for use on rabbits; the preferred rabbit poison is the first-generation AR (FGAR) pindone, which didn’t even show up in the sampled eagles, likely because of its rapid decay rate.

Pay and his co-authors suspect that SGARs are moving through native food webs, resulting in tertiary poisoning of the eagles: “The wedge-tailed eagle preys upon several carnivorous species that are known to consume synanthropic rodents [like rats and mice]… The potential for SGARs to move through multiple trophic levels may therefore be causing extensive contamination of Tasmania’s terrestrial food chains.”

Reptiles like blue-tongued skinks are potential sources. Previous research by Damian Lettoof and Michael Lohr in Western Australia identified snakes and lizards as “toxic time bombs” because of their tolerance of AR levels lethal to mammalian and avian predators. Some lizard species eat rodents; others are known to enter bait boxes and consume poisoned bait.

The association with land use and human population density is suggestive. Apart from AR use on crop-eating rodents, the authors note that residential development on Tasmania’s wildland/urban interface may be a factor: “Although human population growth has been relatively low in Tasmania for the past two decades, there has been an increase in the number of residences build in more rural and natural areas… Such practices may introduce ARs into more natural areas.” “In Australia most SGARs are readily available in supermarkets and are unregulated,” says co-author Amelia Koch, affiliated with the University of Tasmania and the Tasmanian Forest Practices Authority. Flocoumafen is registered for agricultural use, but Koch adds that there’s nothing to stop a member of the public buying it from an agricultural shop. No one tracks rodenticide sales or use in Tasmania or Australia as a whole. While the wedge-tailed eagle as a species isn’t at risk in the rest of Australia, the Tasmanian subspecies has suffered from habitat loss and human persecution and is listed as endangered. A recovery plan issued in 1999 estimated a total population of less than a thousand individuals. SGAR poisoning could push these raptors over the edge. They’re not the only wildlife in peril: according to Nick Mooney of Birdlife Australia, rodent specialists like the threatened Tasmanian masked owl (a relative of the barn owl) and the Tasmanian boobook owl are highly vulnerable. Accipiter hawks like the threatened gray goshawk may prefer birds but, like the North American Cooper’s hawk, will take the occasional rodent. While there’s little or no data on carnivorous mammals, Koch says endangered marsupials like Tasmanian devils and weasel-like eastern quolls “are almost certainly exposed.”

Public outreach and regulatory changes are urgently needed to prevent another Tasmanian tragedy.